Development of span across Columbia River entailed visionary leaders, hard-fought legislative battles, setbacks

In late June 1905, Vancouver Mayor E.G. Crawford boarded a crowded ferry from Vancouver to Portland among an excited group. They were heading to Portland’s 1905 Lewis and Clark Exposition, an unofficial World’s Fair that drew 40,000 visitors on the first day.

Crawford made his way through the crowds and the white-painted buildings, joined by 2,000 Vancouverites. In front of a crowd coming to celebrate the opening, Crawford approached a microphone to welcome the guests. It didn’t take long for him to speak about Vancouver’s growth, made more obvious by the Vancouver residents in the crowd waving banners that read “Vancouver grows without watching.”

“The population of Portland will double within the next decade, and I can see no reason why Vancouver should not keep pace,” Crawford said.

Enlarge

The Columbian files

However, there persisted one major issue with Vancouver, one that was surely still on Crawford’s mind earlier that day.

So many cars and pedestrians had tried to take the ferry across the Columbia River that morning that a blockade formed, even with backup boats to help the one ferry in service.

So standing before the crowd, Crawford saw the fair as an opportunity to illustrate the need for a bridge connecting the two states.

“We expect to have a bridge across the Columbia within the next few years,” he said to the onlookers.

The story of what happened next will sound familiar to modern Clark County residents. There were huge struggles: funding issues, questionable political motives, failed votes and construction disasters that killed workers.

But eventually, the steel bridge connected the two states to a massive celebration. It made both states and cities more prosperous, and it gave Vancouver a landmark that’s stood for over 100 years.

Enlarge

The Columbian files

Ferry system

Ages before the Lewis and Clark Expedition paddled down the Columbia River and passed what’s now Vancouver, Native Americans had been using canoes carved from trees to travel across the river that, at times, ran thick with salmon.

The Chinook people called the river “Great Water,” according to a 2016 Portland State University paper called “Chinookan Villages of the Lower Columbia.”

Settlers at the Hudson’s Bay Company’s Fort Vancouver also used canoes and boats to travel across the river in the 1800s, when supplies and furs were ferried between the two lands.

The first ferry service between Vancouver and Portland started in 1846 — seven years before the Washington Territory was incorporated. The ferry mainly carried foot traffic, operating sporadically for about a decade. In 1855, the fee to cross was 50 cents for a pedestrian, and costs increased depending on what animals were accompanying.

Eventually, more ferries began service; at this point they were powered by steam. At least three short-lived operations shuttled people between Vancouver and Portland, but the only lasting ferry was the Veto, which began operations in 1880.

The Veto gave way to Veto No. 2 after two years. At 90 feet long and 24 feet wide, it “was the nearest approach to a real ferry that had been constructed up to that time,” according to the Fort Vancouver Historical Society of Clark County.

The Albina No. 2 replaced the Veto No. 2 in 1883. During the Albina No. 2’s 10-year run, it became clear travelers needed a larger ferry because people were often left on the bank, the ferry being too small to carry them all.

A new boat, the Vancouver, began service in 1893. It caught fire and was nearly destroyed in 1899. It took roughly $1,500 — around $50,000 today — and several months for workers to refurbish the craft.

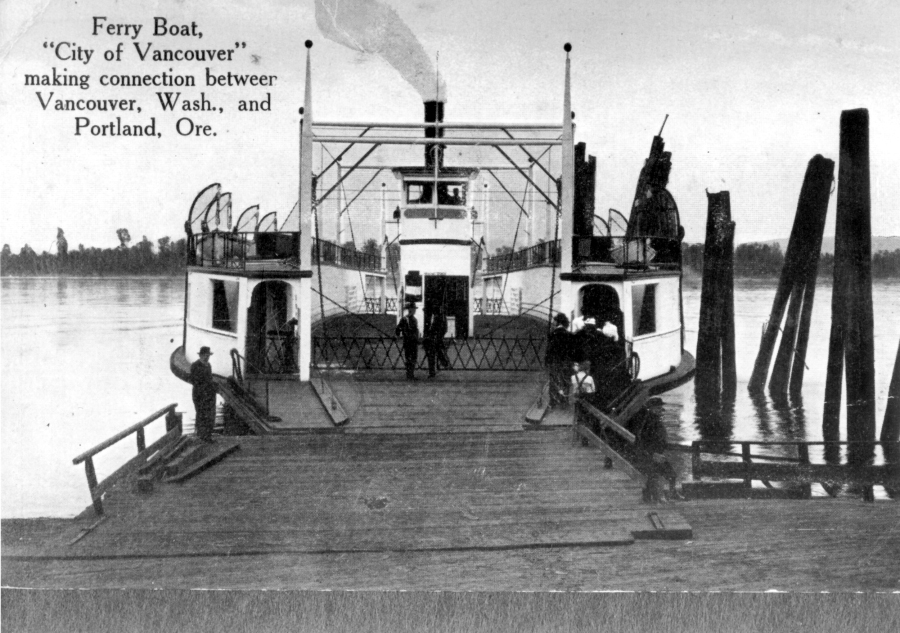

The City of Vancouver ferry replaced the Vancouver in 1909. The Portland Railway Light & Power Co., which operated the City of Vancouver, had a monopoly because it controlled rights to the docks on Portland’s side and would not let anyone else use them.

Because of their monopoly, when Portland Railway Light & Power asked Vancouver for a five-year license to continue operating its ferry, Vancouver granted it for only six months, to hedge against fare hikes.

After the six months were up, Portland Railway Light & Power again asked for a five-year license, and it was granted a one-year license instead. When that was up, it received a three-year license and began to push its fares up.

The City of Vancouver operated for eight years, its last run coinciding with the opening of the Interstate Bridge.

Enlarge

The Columbian files

Funding troubles

In December 1913, Rufus Holman “pledged himself to do everything in his power toward securing the completion of the bridge within the next two years,” according to an article in The Columbian’s archives.

After being elected Multnomah County commissioner in 1913, Holman became chairman of the Joint Bridge Commission between Clark and Multnomah counties. He held a variety of jobs before becoming a commissioner, including working as a schoolteacher, bookkeeper, accountant and auditor.

His role now was to ensure that the bridge became reality.

Four years earlier, the first real push to build a bridge began from business clubs on both sides of the river.

Vancouver’s Commercial Club and Portland’s East Side Business Men’s Club urged their state legislatures in 1909 to appropriate $5,000 — roughly $86,000 today — for preliminary surveys and cost estimates of a bridge.

The measure appeared before the legislatures that year. It passed in Washington’s Legislature but narrowly failed in the Oregon Senate 14-12.

“The men who voted ‘no’ with reference to this project voted in ignorance of the issues, or, knowing the facts chose to vote against what would have been sound public policy,” The Columbian read the day after the vote in the Oregon Senate.

The failed vote delayed the process for three years.

Enlarge

Clark County Historical Museum Photographs Collection

A bridge spanning the Columbia had been discussed for ages, however for most of it, a “wagon bridge” was the bridge of choice.

Former president of the Portland Commercial Club, J.H. Nolta, was one of the first advocates for a larger, more durable span, according to research done by Oregon Department of Transportation historian Robert Hadlow.

“We should not build the bridge for today, next week or next year, but for the next 40 years,” Nolta wrote in 1912.

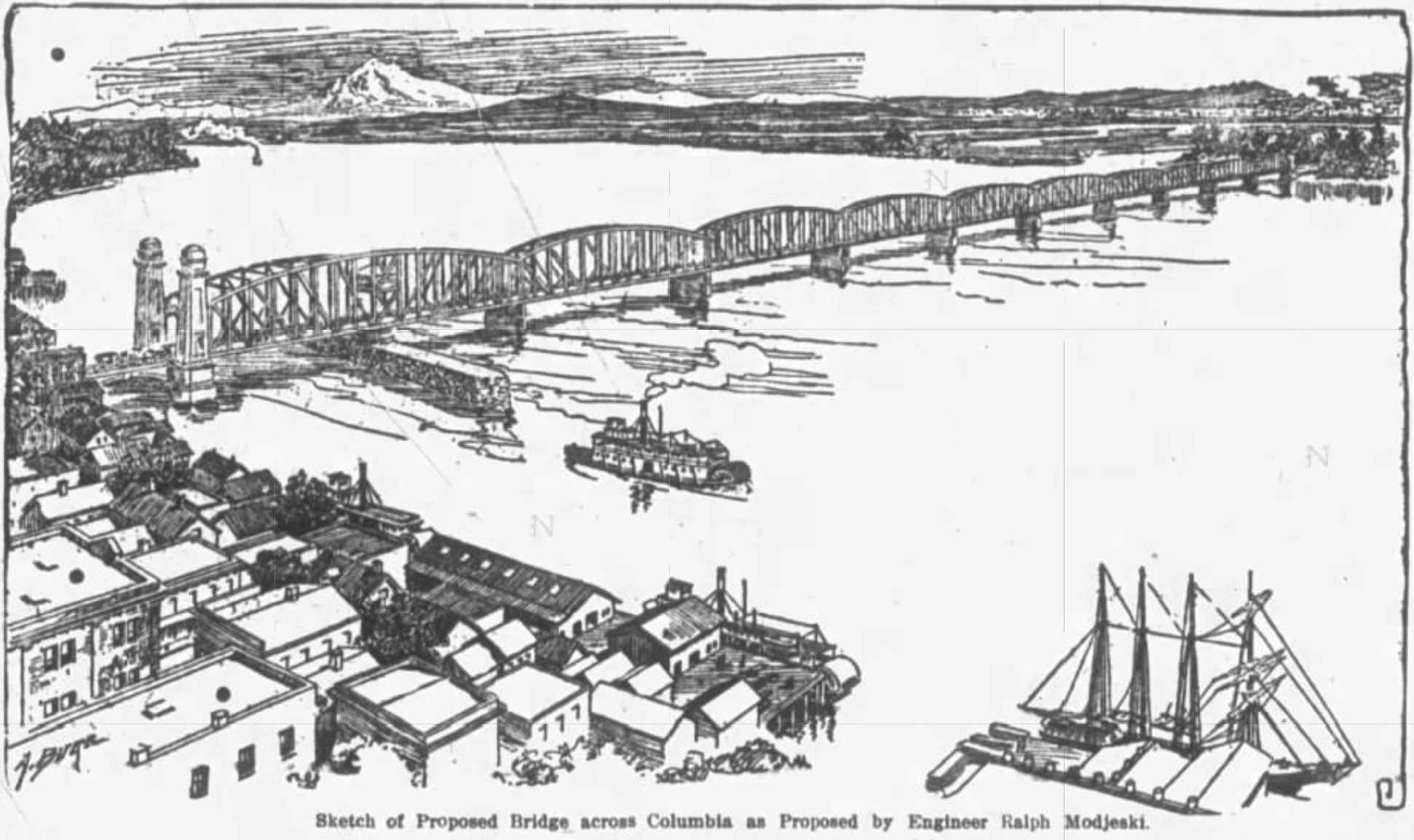

In 1912, the Commercial Club raised the money on its own: $2,500, half the cost of what it would take to get a survey done. Club members then went to Portland to find the other half.

The sound of Scottish bagpipes flooded Portland the morning of March 2, 1912, as 300 Vancouverites rallied throughout the city calling for them to match Vancouver’s half and bearing banners that read: “We want the bridge, and so do you. We’ve done our part. Now you come through!”

The Portland business community heard the message and matched Clark County’s $2,500. By April 1, engineer Ralph Modjeski was selected to conduct preliminary bridge surveys and cost estimates.

Enlarge

Clark County Historical Museum Photographs Collection

Bridge support increased in Multnomah County through the years and, in 1913 after Modjeski completed his study, bills funding the bridge, $500,000 from each state, went before both state legislatures. The bill had the unanimous support of both the House and Senate committees on roads and bridges, and it was passed in the Washington and Oregon legislatures.

In anticipation of the bill passing, Clark County residents organized a celebration and were going to save the pen that Washington Gov. Ernest Lister, a Democrat, would use to sign the bill.

Lister vetoed it instead, holding it until March 13, the night before the session ended, preventing the passage of a new bill. There was not enough support to override the veto.

“There is, in my opinion, not a sufficient necessity or justification for further adding to the taxes on the state the cost of this bridge at the present time,” Lister remarked after vetoing the bill.

Lister’s veto was a setback, but did not stall the process for long. A month after, a resolution passed in Clark County, bonding the county for $500,000 for a toll bridge. Support for the toll bridge was high.

Multnomah County overwhelmingly voted to appropriate $1,250,000 for the Interstate Bridge by roughly a 4-1 margin on Nov. 5, 1913, ensuring, after many setbacks, that a bridge would be built.

Enlarge

Clark County Historical Museum Photographs Collection

Construction and opening

For the bridge’s construction, one of the early decisions the commissioners of Clark and Multnomah counties made proved to be controversial.

The commissioners, led by Holman, received 13 bids from different engineering firms. Kansas-based firm Waddell and Harrington quoted $87,000 — nearly $3 million today — for its services. Even though other firms made identical proposals but offered to charge nearly $30,000 less, the commissioners chose Waddell and Harrington on Jan. 1, 1914, according to The Columbian’s archives.

Their selection drew criticism because of the high price; they didn’t expect the blowback to be so severe.

The Interstate Bridge Commission renegotiated the price down from $87,000 to $65,000, an acceptable compromise, and Waddell and Harrington signed the contract. The firm got to work shortly after, conducting surveys and working to determine the location of the bridge.

“The Interstate Bridge board ought now to be aware that there is emphatic general disapproval of the proposed award of the bridge contract to the highest bidder,” according to an article from The Columbian on Jan. 5, 1914.

Clark County agreed to pay for two-sevenths, or $500,000, of the bridge. Multnomah County, because of its larger population, would pay for five-sevenths, or $1,250,000, of it.

Soon after, another issue developed: as bonds were advertised and ready to be sold, the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand and the onset of World War I delayed the sale of bonds until November, delaying construction.

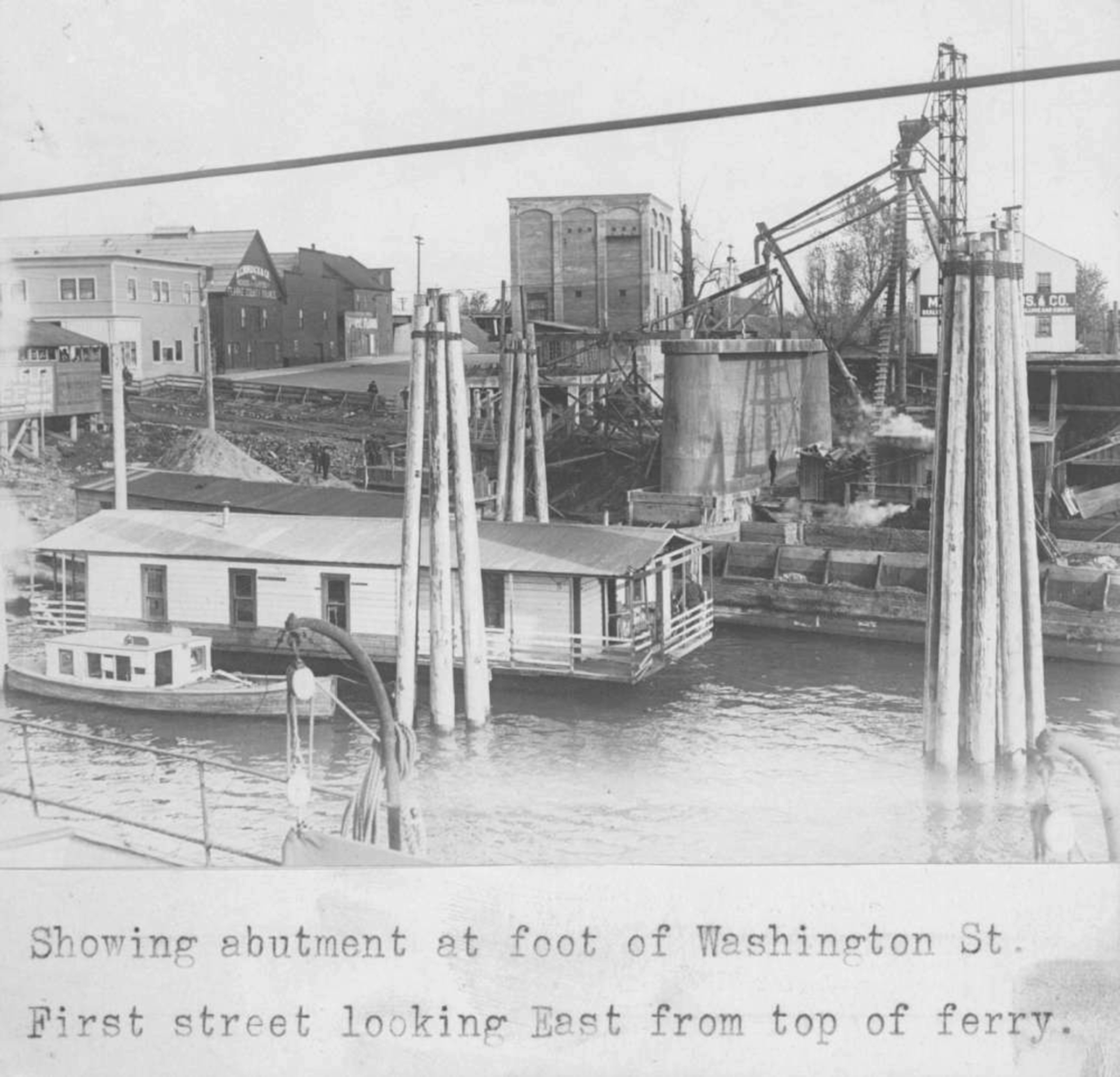

Construction of the bridge finally started in March 1915 with a groundbreaking ceremony attended by hundreds.

The Columbian called it “the greatest event in the history of the two cities.”

Construction progressed faster than expected. Workers completed the pile driving by July, allowing docks to be floated into place.

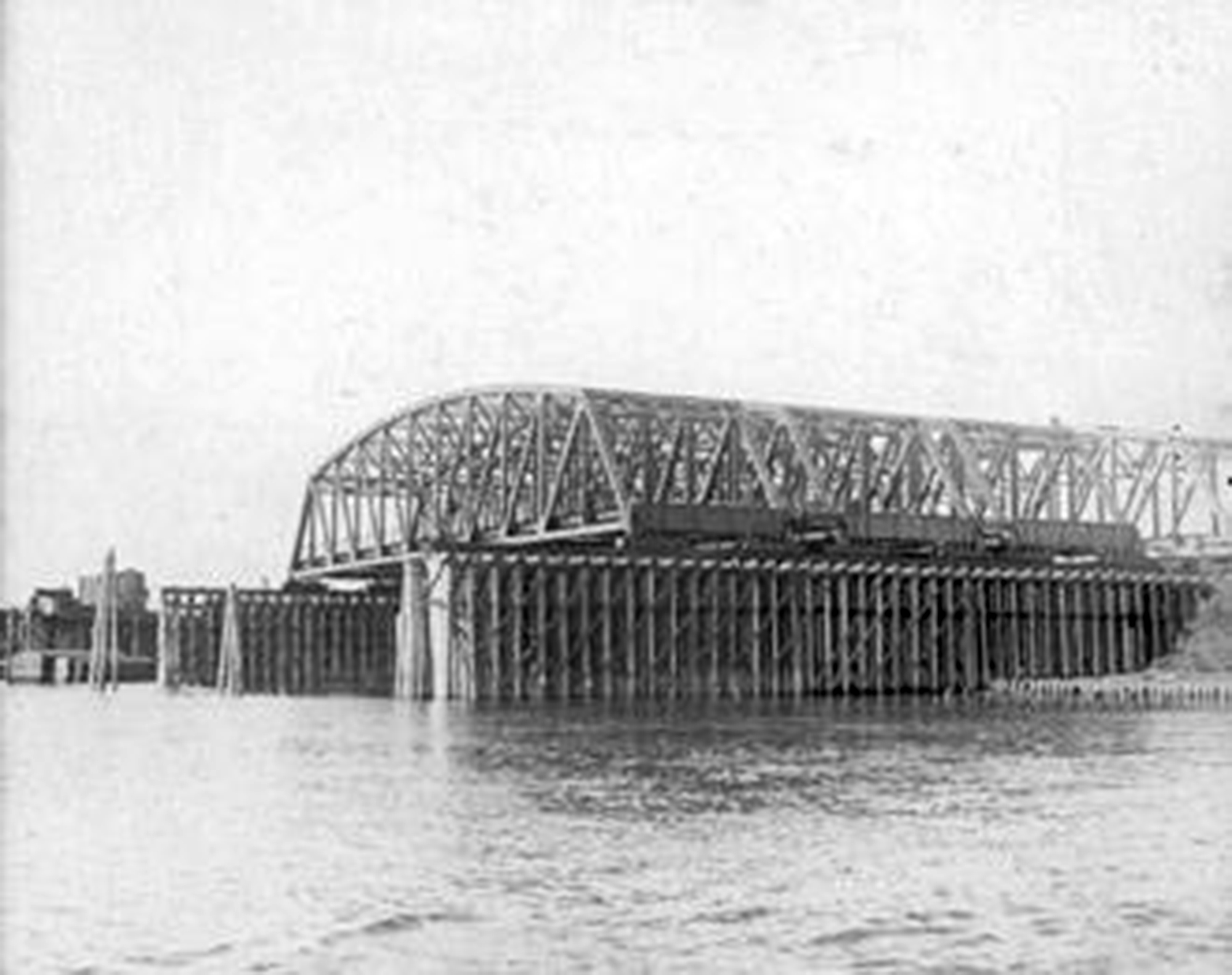

By the end of the year, the bridge was three or four months ahead of schedule. Boats floated the first metal span into place in April 1916 with three more in place and paved by the end of the month.

Enlarge

The Columbian files

The construction was dangerous work that caused more than one catastrophe.

On April 27, 1916, while boats moved the draw span during a windstorm, a strong gust wrestled it from three tugboats and flung it 60 feet, smashing it into a derrick scow, a flat-bottomed vessel used for carrying equipment, and piling dolphins, pilings grouped together in an array serving as a protective hardpoint along a dock. They likely saved several lives.

During another event, two people died by drowning: one fell through open steelwork and drowned in the river, and the other drowned after he stepped off of a scow where he was unloading lumber.

Another worker fractured his skull after falling 25 feet from one of the spans.

In December 1916, two months before it was officially completed, there was an unexpected soft opening of the bridge.

When the Columbia River froze Dec. 30, 1916, ferry service was canceled and pedestrians were allowed to walk over the nearly completed bridge.

The bridge officially opened on Feb. 14, 1917, and was welcomed by up to 50,000 people, the biggest crowd Vancouver had ever seen. The city’s population was about 12,000 that year.

Separate parades starting in Portland and Vancouver met in the center of the bridge, where a handful of brief speeches took place. The ribbon was cut, and Vancouver and Portland physically connected for the first time. The headline in The Columbian read, “With Iron Bands We Clasp Hands.”

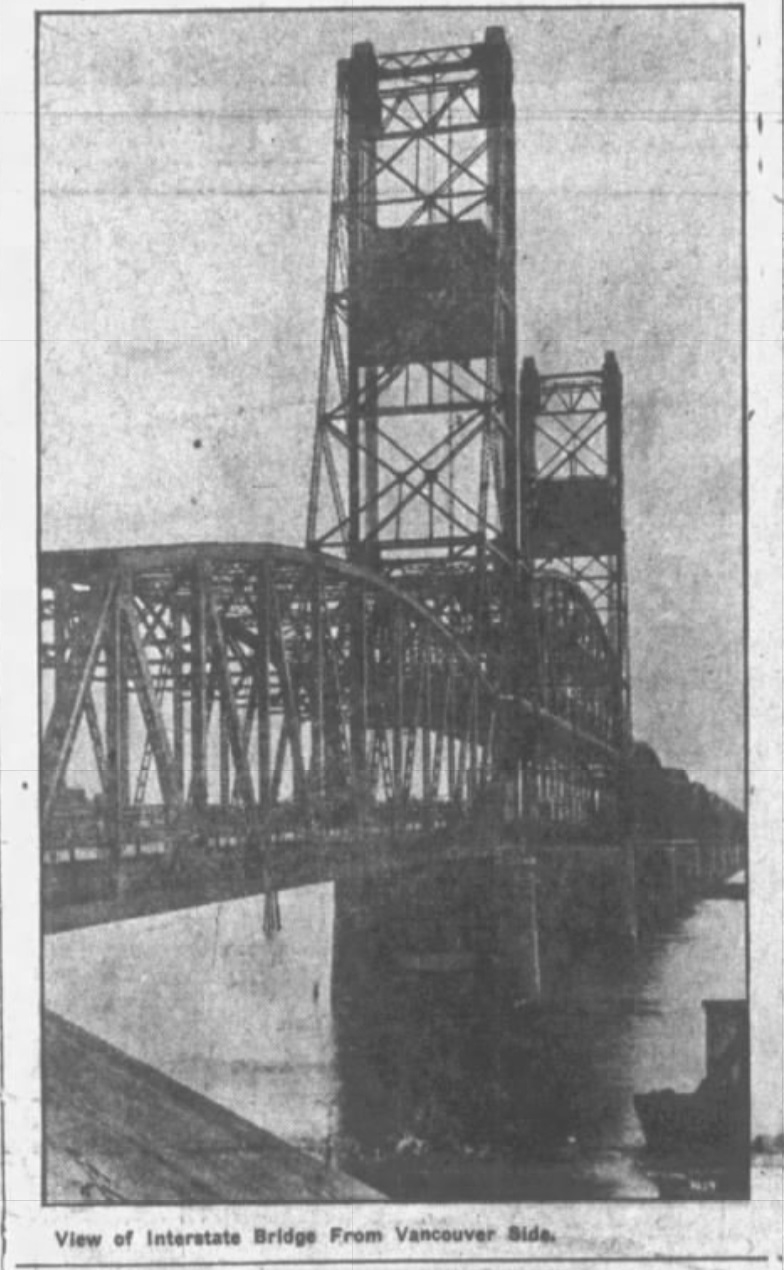

The bridge sat at 3,500 feet long with a 38-foot-wide roadway, enough room for two directions of traffic. It also came equipped with two sets of streetcar tracks, connecting streetcar service from Portland to Vancouver.

“The last unfinished link in the Pacific Highway was welded today, and the welding of that link in the great highway became one unbroken artery of commerce,” The Columbian wrote.

For the first time, travelers could take the Pacific Highway from Mexico to Canada without having to take a ferry.

It surely seemed like a struggle to fund and build the bridge, but the problems of operating, repairing and expanding the green-painted drawbridge, at a time when Clark County’s population was multiplying, would continue for more than a century.

This story was made possible by Community Funded Journalism, a project from The Columbian and the Local Media Foundation. Top donors include the Ed and Dollie Lynch Fund, Patricia, David and Jacob Nierenberg, Connie and Lee Kearney, Steve and Jan Oliva and the Mason E. Nolan Charitable Fund. The Columbian controls all content. For more information, visit columbian.com/cfj.

This story was made possible by Community Funded Journalism, a project from The Columbian and the Local Media Foundation. Top donors include the Ed and Dollie Lynch Fund, Patricia, David and Jacob Nierenberg, Connie and Lee Kearney, Steve and Jan Oliva and the Mason E. Nolan Charitable Fund. The Columbian controls all content. For more information, visit columbian.com/cfj.

For more history of Clark County visit newspapers.columbian.com